Programmatic: Break It Down To Build It Back Up

“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Tom Triscari, co-founder and managing partner at Labmatik.

The best project engagement I ever experienced started with an unambiguous CMO mandate.

“I am going to make it simple for you guys,” she said. “I want you to break everything down and build it back up. There is a big difference between spending budget and doing great advertising. We are either going to use programmatic to do great advertising once and for all, or we will kill it.”

Like most big advertisers, this client’s programmatic budget had subtly ballooned to hundreds of millions over a few years. And like many CMOs, she was going through what Mastercard’s Raja Rajamannar calls an “existential marketer crisis.”

Our CMO suffered from cognitive dissonance: “Why have we escalated commitment to programmatic, which I’m told is the place to be, when all I read in the trade press and hear at conferences is one bad story after another?”

She was perplexed yet hopeful. She knew enough to know that programmatic was not functioning as sold, and yet she wanted all these algorithmic and data tools to finally get the advertising job done better, faster and cheaper. She also wanted empirical proof to match the sales pitch.

‘It’s time to create a new media supply chain’

Marc Pritchard recently called for a new media supply chain that “levels the playing field and operates in a way that is clean, efficient, accountable and properly moderated for everyone involved.”

While having such high aspirations is a great first step, the next step for marketers — from the most junior programmatic traders to the CMO — is to level-set on a hard-to-accept trade-off: When advertisers force budget pacing through programmatic, they unknowingly do so in exchange for low impression quality standards.

Acknowledging this terrible trade-off is the first step toward reimagining programmatic supply chains.

The trade-off

Forcing media budget through inventory of unknown quality is the primary cause of advertiser woes with programmatic.

Once budgets get cut for particular channels such as programmatic, which increasingly takes an ever-larger share, the day-to-day drill for supply chain partners is to ensure it gets spent. If “use it or lose it” budgets are not exhausted by the end of the campaign, the programmatic ecosystem players, who mostly get paid on a percentage-of-media basis, make much less money.

Advertisers also want to buy the highest ad quality possible — brand safe and highly viewable ads served to humans. This basic advertising need could not be more straightforward, yet programmatic has consistently underperformed across the board.

The heart of the ad quality issue starts at the very origins of how publishers sell remnant inventory into programmatic auctions. The unsold or unsellable inventory is set up as a low priority in the publisher’s ad server (priority eight or 12 in Google Ad Manager, for example). This means the best users and impressions are already taken. Once advertisers gain access to more accurate and transparent information on impression quality before submitting bids, they have a good shot at leveling the playing field and solve the information asymmetry that plagues today’s supply chain.

If exhausting media budget is the top priority, then advertisers must accept lower ad quality despite the unrealistic and unprovable promises sold by a long list of intertwined supply chain actors.

If maximizing true ad quality is more important, then advertisers must accept that they can’t spend the entire budget. However, since exhausting budget typically squashes all the other optimization features and options built into DSPs, advertisers end up subjecting themselves to an artificial constraint. This in turn acts as a lubricant for the ecosystem, but ultimately continues to cause advertiser dissatisfaction.

In other words, if all you have is a hammer (budget pacing), then every optimization problem looks like a nail.

Breaking bad

Until this bad trade-off is corrected, advertisers should not expect their programmatic aspirations to catch up to oversold promises.

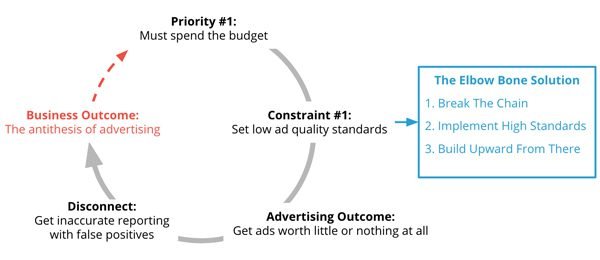

The “Elbow Bone Solution” illustrates why the trade-off exists. It’s based on the old joke: A guy goes to his doctor, moves his arm up and down, and says “Hey doc, it hurts when I do this.” The doctor replies, “Then stop doing that.”

The Elbow Bone Solution

The same goes for advertisers trying to overcome the cognitive dissonance of a bad trade. Stop doing the thing that causes so much dissatisfaction. The better course is to raise ad quality standards.

Advertisers will either get the ad quality they expect by injecting high standards or they should stop buying. If programmatic cannot deliver against high standards, then stop relying on it until works for you.

‘If you want something new, you have to…