Europe’s GDPR has accomplished a lot in its infancy

At just a year old, the General Data Protection Regulation has already forced big tech firms to make significant changes to their privacy policies. And its real effects are still to come.

Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, which celebrates its first birthday Saturday, has managed to do a lot as a tyke.

The GDPR changed the rules for companies that collect, store or process information on residents of the EU, requiring more openness about what data they have and who they share it with. The law is hailed as the global standard for privacy in the digital age, in which data is a precious commodity.

The GDPR came into effect a few months after the news broke that political consultancy Cambridge Analytica had gotten ahold of personal data on 87 million Facebook users without their permission. The timing emphasized the need for the GDPR and highlighted that it was overdue.

The law has forced Facebook and its Silicon Valley neighbors to make sweeping changes to their privacy and data-handling policies, such as asking users to consent to new terms and bringing in pop-ups to inform them of any changes. Importantly, it introduced special protections for teenagers. So far, only one US company, Google, has been hit with a major fine.

For the big US companies, the real effects of the GDPR are still to come. The EU’s move to update its privacy regulation has spurred other countries around the world — including Silicon Valley’s home turf — to consider following suit. And because it’s been used sparingly in its first year, tech companies big and small still haven’t felt the force of the regulation.

Complaints and fines so far

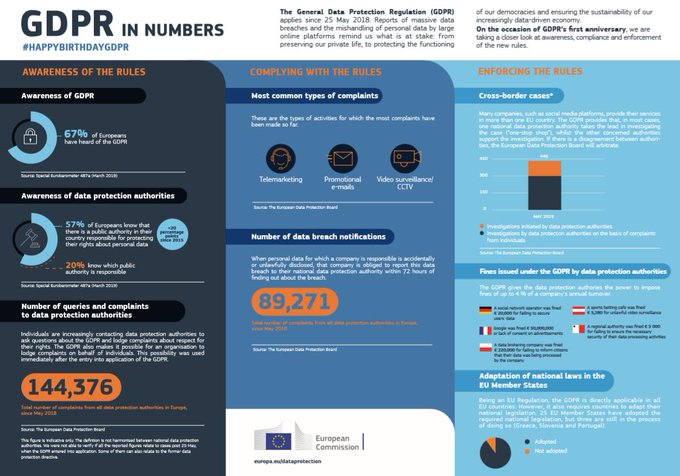

According to EU figures, citizens, privacy organizations and others have filed 144,376 GDPR complaints since the regulation came into force. (Complaints can be submitted by any people who feel their privacy has been impacted.) Companies have reported 89,271 data breaches, which they’re obligated to report within 72 hours of discovery.

Fines, however, have been much smaller than expected. Under the GDPR, companies can be fined 20 million euros ($22.4 million) or 4% of their total annual worldwide revenue in the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.

In January, Google earned the only landmark GDPR penalty thus far when French regulators handed out a 50 million euro fine to the tech giant for not properly disclosing to users how their data is collected and used for targeted advertising. Google still faces an open probe, announced this week by the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC).

“We will engage fully with the DPC’s investigation and welcome the opportunity for further clarification of Europe’s data protection rules for real-time bidding,” said a Google spokesman in a statement. “Authorised buyers using our systems are subject to stringent policies and standards.”

Other notable fines have been issued by data protection authorities in Portugal (400,000 euros to a hospital), Poland (220,000 euros to a data processor that scraped the internet) and Germany (20,000 euros to a chat app aimed at children). There’s currently no record of the total number of fines issued.

The storm is coming

Marc Dautlich, a partner at Bristows law firm, says the cautious start makes sense because data protection authorities have to learn how to wield their new powers.

The authorities are wrestling with the “official interpretation” of the new law, he said. This has meant consulting with one another, as well as with law firms and privacy organizations.

With an increase in the number of complaints to investigate — Ireland’s DPC has seen complaints more than double since the GDPR was introduced — has come a need to hire more staff.

Issuing fines hastily would also cause problems for data protection authorities. Armed with massive teams of lawyers, tech giants will push back on anything they find unfair, as they have done against EU antitrust decisions. And authorities need to staff up because of the increase in complaints.

Dautlich said the watchdogs will prioritize complaints involving AI, facial recognition, data profiling and ad personalization. That’ll affect Silicon Valley, because most of these technologies aren’t homegrown in Europe.

Ireland has an ongoing list of investigations into a who’s who of tech titans to see if they’re complying with the GDPR. The targets include Twitter, Apple and Facebook (as well as Facebook’s Instagram and WhatsApp services). None of the companies was willing to comment on the record about the open investigations.

It might seem as though it’s in the EU’s interests to secure in the early days a plethora of high-profile fines meant to ensure that tech companies across Europe and the globe continue to take compliance seriously. But even the European Commission is more concerned about the how than the when.

“Compliance is a dynamic process and does not happen overnight,” Věra Jourová, the European Justice Commissioner, and Andrus Ansip, VP for the EU Digital Single Market, said in a joint statement this week. “Our key priority for months to come is to ensure proper and equal implementation in the Member States.”

The big tech companies are also waiting for more clarification on how the regulation should be implemented. “As lawmakers adopt new privacy regulations, I hope they can help answer some of the questions GDPR leaves open,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote in a blog post in March. “We need clear rules on when information can be used to serve the public interest and how it should apply to new technologies such as artificial intelligence.”